Notre cathédrale a toujours représenté une énigme. Enfant déjà je tentais de percer le secret de ce monument, et aujourd’hui encore, chaque fois que mes pas me mènent dans sa proximité, je la contemple, muet devant le spectacle de cet exploit réalisé par ses bâtisseurs, portés par une foi profonde.

Mon métier d’architecte m’a aidé à comprendre les difficultés rencontrées à l’époque par les constructeurs. Alors, depuis quelque temps, je me suis mis à peindre cette cathédrale qui reste une éternelle source d’enchantement et de découverte.

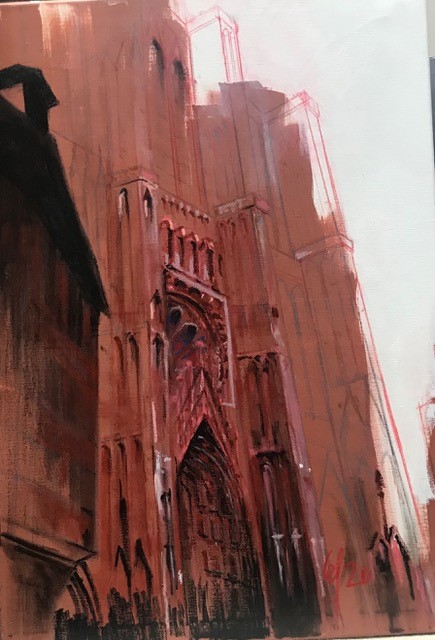

25 toiles n’ont pas calmé ma curiosité qui se traduit sur des toiles de format 65 x 92 cm, d’une technique mixte consistant à utiliser de la peinture acrylique et à l’huile. Mon but n’est pas de réaliser une image fidèle du monument, mais de transmettre ce que je ressens lors des nombreuses observations. En voici deux exemples ; l’un représente une cathédrale en cours de construction, l’autre met l’accent sur la couleur utilisée à l’époque pour relever les éléments architecturaux et les sculptures.

Albert-Georges Mehl